In today's TPOM, we will be looking at ordered thinking, first, second, and third-order thinking, how to build a thinking order map that details first-order through third-order thinking, and how that can become the scaffolding for other types of maps, such as a causal map.

Ordered Thinking

Ordered thinking is much like it sounds. It is simply taking your thinking and establishing a coherent, cohesive, and cogent system of thought that covers the essential components of thinking so that you can be sure that you are learning the subject of the inquiry with confidence. If appropriately applied, ordered thinking will go a long way in ensuring that you are not laboring in vain only to come away with illusory competency in your field of study. We will contrast this in the future with higher-order thinking, which takes ordered thinking to new heights. You will notice some overlap between these two important concepts as we progress. Be mindful to pay attention to the areas of overlap as well as those of differentiation. More to come about all of that in a later installment. Onward!

The following is a list of the critical components of ordered thinking:

Critical thinking

Inference

Comprehension

Application

Evaluation

Synthesis

Metacognition

Critical Thinking

The following is an excellent definition of critical thinking:

"Critical Thinking as Defined by the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, 1987

The following is a statement by Michael Scriven & Richard Paul that was presented at the 8th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform, Summer 1987."

"Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.

It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue; assumptions; concepts; empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions; implications and consequences; objections from alternative viewpoints; and frame of reference. Critical thinking — in being responsive to variable subject matter, issues, and purposes — is incorporated in a family of interwoven modes of thinking, among them reside scientific thinking, mathematical thinking, historical thinking, anthropological thinking, economic thinking, moral thinking, and philosophical thinking.

Critical thinking can be seen as having two components: 1) a set of information and belief-generating and processing skills, and 2) the habit, based on intellectual commitment, of using those skills to guide behavior. It is thus to be contrasted with: 1) the mere acquisition and retention of information alone because it involves a particular way in which information is sought and treated; 2) the mere possession of a set of skills because it involves the continual use of them; and 3) the mere use of those skills ("as an exercise") without acceptance of their results.

Critical thinking varies according to the motivation underlying it. When grounded in selfish motives, it is often manifested in the skillful manipulation of ideas in service of one's own or one's group's vested interest. As such, it is typically intellectually flawed, however pragmatically successful it might be. When grounded in fairmindedness and intellectual integrity, it is typically of a higher order intellectually, though subject to the charge of "idealism" by those habituated to its selfish use.

Critical thinking of any kind is never universal in any individual; everyone is subject to episodes of undisciplined or irrational thought. Its quality is, therefore, typically a matter of degree and dependent on, among other things, the quality and depth of experience in a given domain of thinking or with respect to a particular class of questions. No one is a critical thinker through and through, but only to such-and-such a degree, with such-and-such insights and blind spots, subject to such-and-such tendencies towards self-delusion. For this reason, the development of critical thinking skills and dispositions is a life-long endeavor."

Inference

Inference is the action or process of inferring, the drawing of a conclusion from known or assumed facts or statements, and, especially in Logic, the forming of a conclusion from data or premises, either by inductive or deductive methods. It is reasoning from something known or assumed to something else that follows from it logically speaking.

If you are walking through a field and you look down and see a stopwatch lying in the grass, you might infer that the stopwatch was dropped by someone accidentally. If it were a gold stopwatch, you might especially infer that it was dropped by someone accidentally. Why the "especially?" It is easy to think that someone lost their stopwatch in either case. However, a case can be made that the more valuable the stopwatch, the less likely most people would be to lose it in the field, as the preciousness of an object usually translates to one's care and protection of that object. Thus, it would lend a slight weight to the inferential proposal that the stopwatch would most likely have been lost. It would be less likely that the stopwatch had been thrown away into the field due to its value. It would be less likely that the stopwatch had been stolen, and the thief would go through all of the trouble to steal it only to throw it away. In that case, it would be more likely that the thief dropped it while absconding.

Note that in the above, it is fairly easy to come up with many contradicting propositions to what I have proposed. Since we are dealing with inferences from a position lacking in conclusive knowledge and that position thus necessitating the use of the inference in the first place, it is thereby all open to what people choose to infer. That being said, it says nothing of the level of accuracy of the inferences or the probabilities of common events happening in higher numbers than uncommon ones. In the case of the latter statement, it still remains most likely that the stopwatch was dropped, though an amazing story containing many outliers is still possible, just not "as" probable.

If you think about this one, you will get a very solid grasp of what inference is and how to use it well.

William James: “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.”

Comprehension

Comprehension is as follows:

The act or fact of grasping the meaning, nature, or importance of; understanding.

The knowledge that is acquired in this way.

Capacity to include.

Comprehension is a higher-order thinking skill. In order for one to comprehend anything, one must have gained an understanding of that thing and internalized it to the point of grasping the importance of the content. This means that comprehension is not a dry act to be "checklisted" and, therefore, thought to have been obtained once one can recite the concepts back by rote. This goes much deeper than that and drives into the nature of the thing such that the source-level importance of the thing is internalized. If this is done properly, one would then be able to not only understand the thing, but one would be able to traject outward from that thing with clarity, concision, and high levels of accuracy.

That all being said, there are levels of comprehension. However, for one to say that they comprehend X or Y subject means that they are at the source level and can do all that I wrote about in the above explanation of comprehension.

Confucius: “Learning without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous.”

Application

Application regarding higher-level thinking skills means the following: Application is the ability to understand that one's surface abilities are underpinned by substructural abilities or substructural matrices of required constituents and to use the power of the substructural formations, thus applying them successfully to other tasks that seem proximally or distally related on the surface but are, in fact, highly similar at the level of the core scaffolding. If one can do this successfully, they are said to possess application within this context.

Said another way, once one has acquired X skill, they should be able to apply the traits or constituent components of X skill to another problem or discipline. For example, a race car mechanic has developed many skill sets to be highly effective at the types of fine-tuning required to make a race car run at top levels of output consistently. If one could not do this, they would not be considered a race car mechanic for very long.

The plethora of meticulous skills the mechanic had to develop should be able to be used in other applications across the spectrum of their life needs. They should be able to apply these skills to carpentry to some degree, mathematics, critical thinking systems, systems thinking, and the like. When this is not present within the mechanic, they are not considered to have the higher-order thinking tool of application. If one could apply their systematic thinking learned from troubleshooting the complexities of the types of issues that could arise from a race car engine and apply the scaffolding or core of that type of systematic thinking to another discipline, then they would certainly be said to possess the higher-order thinking skill of application.

Evaluation

Evaluation is a concept that is very close to critical thinking and, indeed, needs to have components of critical thinking within its makeup, or it will cease to be evaluation. Evaluation is the process of taking in data and filtering the data to yield specific outcomes. Some may argue that it is only the latter, but the process of evaluation is happening even in how the data arrives, at least in the situations I encounter daily; thus, I classify it as holding both parts of the above statement.

A key component of evaluating anything is to understand what you are evaluating, why you are evaluating it, and what process of evaluation will ensure honest outcomes. Here is the part where science for hire shows up and squeezes out whatever conclusion X patron wishes to set forward upon the world. You need to say 7 out of 10 Y's agree and that P is the best X. Well, you have come to the right place. We can use the process of evaluation and filtered statistics to get you where you need to go! For a hefty price, of course.

Evaluation in its pure form is nothing more than the careful application of thinking systems of analysis applied to a subject to verify it for X or Y outcome, trait class, usage, context, or the like. In fact, you are evaluating this writing and likely me to some extent as you read this essay.

It is not whether or not we will evaluate but whether or not we will evaluate well.

Synthesis

Synthesis in the context of higher-order thinking deals with the bringing together of two or more separate ideas into a new idea that is meritorious or of high usage or value.

A somewhat hilarious example of this is the old late 1970s commercial for Reese's Peanut Butter Cups. There is a fade-in of a young person with a jar of peanut butter and another young person with a chocolate bar. Soon, they bump into each other, and the chocolate bar finds its way into the peanut butter jar. The young person pulls out their now peanut butter-covered chocolate bar, looking despondent. Rather than lose the chocolate bar, they take a bite and boom! Synthesis! The chocolate and the peanut butter, each a good idea in their own right (work with me some here; everything can't always be dry and academic), have now been synthesized into the single food soon to be known as the Reese's Peanut Butter Cup. They both decide to share their newfound discovery, and unlike today there was no ensuing lawsuit for discovery and copyright ownership. They just enjoyed the food and had a good day.

Metacognition

Metacognition, in short, is the ability of one to understand one's own thinking processes and to accurately assess one's strong and weak areas, along with the ability to apply the aforementioned to any task, study, job, or other application that requires successful self-assessment and macro-structure thinking skills. It comes with three main areas of focus typically, though I consider there to be more present than the typical explanation. There will be more to come on this in later essays. The three areas are as follows:

Planning - the planning phase comes with the following categories: 1. What are you trying to learn? 2. What is the time frame you are working within? 3. What skills do you already possess that can help you in learning this subject? 4. What is the primary focus of the learning, given your specific strengths and weaknesses?

Monitoring - the monitoring phase is to be done continuously throughout the study; it comes with the following categories: 1. Checking for retention. 2. Checking to see whether or not one can speed up or slow down the pace of study. 3. Checking to see whether or not there needs to be further inclusion of study tools, thinking tools, outside help from experts, or the like.

Evaluating—The evaluating phase comes at the end and utilizes all of the data from the monitoring phase, which is itself a form of evaluating. During the evaluation phase, one asks critical questions to assess one's performance and how to improve it in any way possible.

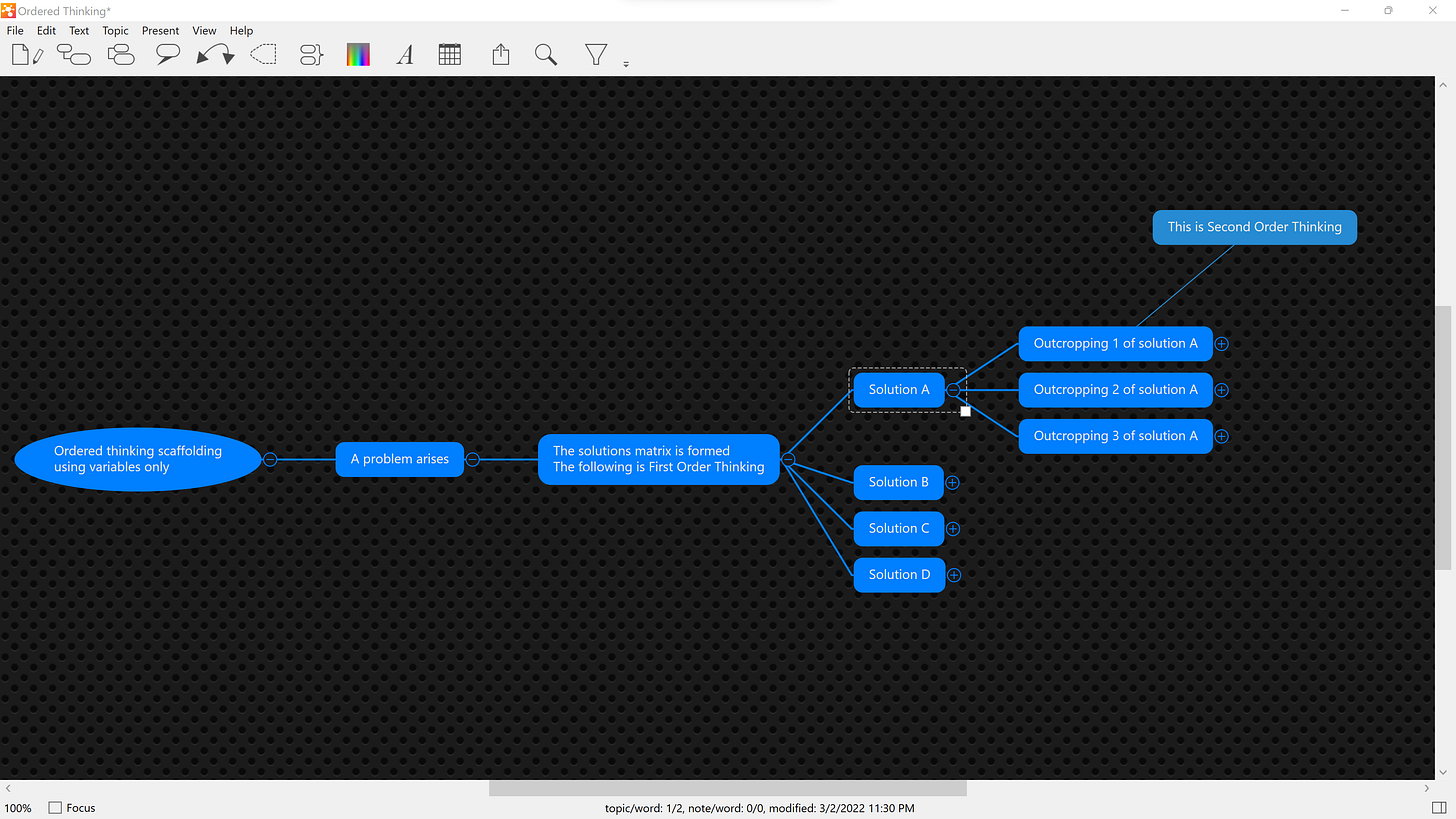

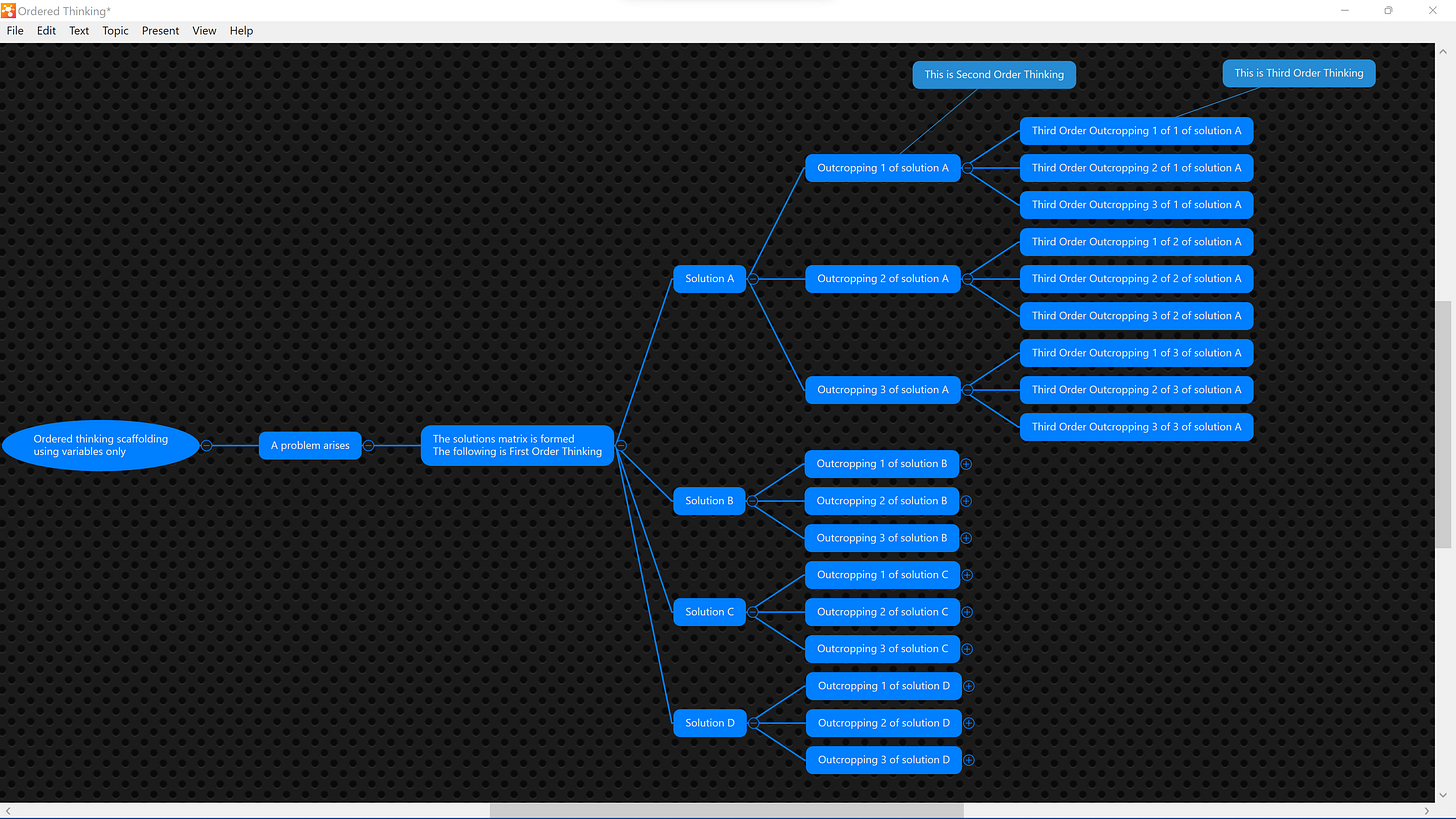

First-Order Thinking

First-order thinking is the thinking that happens upon the arrival of a problem. It deals with the acquisition of the solutions set and with attempting to find the most viable solution. It can be somewhat successfully expressed as X happened, and we now have P problem. What is the solution to P (this is the first-order of thought)? Note you will see varying ways of talking about first-order thinking, don't let that get in your way. Once you have the gist, you will find it easy to understand, even though there are many examples of it on the internet that vary from decent to well done to occasionally outright incorrect. Stick with the above, and you will do great.

Second-Order Thinking

Second-order thinking deals with the outcroppings of the first solutions set. Let's say that we have problem P and solutions A, B, C, & D. We choose solution A, and it generates its natural outcropping series, which in turn has to be dealt with inside of another problem/solution set. Let's say that solution A had the outcropping of 1 of solution A, and now we have to deal with the problem set of the outcropping of 1 of solution A. That level of the outcropping series requires second-order thinking.

Third-Order Thinking

Third-order thinking deals with the natural outcropping series from solution A. In dealing with solution A, we had to pick a solution from the solution set of A. We selected solution 1 of solution A. Now, solution 1 has an organic outcropping set that we then have to deal with, and dealing with that set requires third-order thinking. This continues onward from solution A (first-order); to outcropping 1 of solution A (second-order); to the third-order outcropping 1 of 1 of solution A. Each of these sequences outcrops in order to the nth order if we should choose to take it that far.

The point of first, second, third & nth order thinking is for one to get a handle on outcroppings. Every decision we undertake has a series of outcroppings that flow organically from that decision. If one can hone their thinking significantly, they can more effectively deal with those outcroppings and, therefore, get to their desired goals with greater precision, less loss, less trouble, less harm, or the general overall minimization of any problems. In other words, one would be able to plot a course through difficult environments while minimizing negative impacts. If you can combine a deep understanding of ordered thinking, first through nth order thinking, thinking tools, mental models, biases, fallacies, and heuristics, you will be well on your way to thinking at a much higher level, and therefore, you will have gained the ability to see reality with much greater precision and accuracy.

Causal Maps

A causal map can look exactly like the ones posted above. The main difference is that we would not be charting orders of thought but rather a causality stream where the events and the cause and effect matrices would be illustrated clearly; though there is little difference from the above maps, it is a fact that there can be much greater differences generated as we will see in later installments. There will be much more to come regarding causal mapping. For now, take a close look at the maps I posted, and once they are understood, add your inferences about how you think they could be converted into causal maps.

Coming Next

In the next installment of TPOM, I will detail causal mapping and include a few little surprises to help us with the lateral expansion that is so essential for our development.

We will continue.

B.S.R.

This is exciting! I love the Peanut Butter cup synthesis example! I am struck by the vastness of nth order thinking. It seems overwhelming to try to consider so many outcroppings when making a choice. However, I see the incredible usefulness that would follow and and also the destruction that could be avoided if such a system were to be developed.